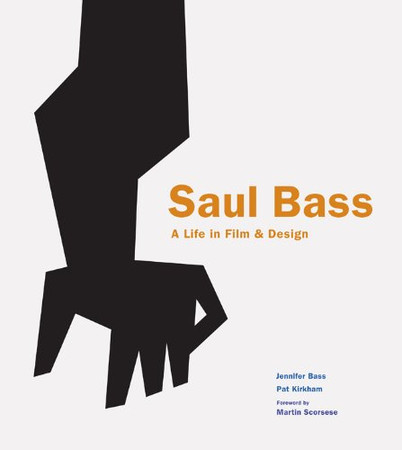

Find the common element among these things: Psycho; United Airlines; Quaker Oats; Dixie Cups; Goodfellas; the Girls Scouts of America. I picked a grab bag, and I could have included a lot more, to show how diverse the work of Saul Bass was; he did graphics, and more, for all of them. There is no bigger name in graphic design than Saul Bass, and now there is a gorgeous book, huge and colorful as befits his career, Saul Bass: A Life in Film and Design (Lawrence King Publishing) by his daughter Jennifer Bass, herself a graphic designer, and Pat Kirkham, who teaches decorative arts and design history. Flip through the 400 big pages here, and you are bound to find logos, posters, and movie title sequences you have seen many times; Bass’s range and influence were astonishing. There is a bit of biography here, along with a relatively chronological summary of his work from his poster for his high school’s open house through the poster for Schindler’s List. The text is worth reading, and the authors have quoted generously from Bass’s own thoughts on his life, work, methods, and output. As befits Bass’s legacy, however, this is a picture book, and it is a treat for the eyes.

Bass was born in the East Bronx in 1920, the child of Jewish immigrants. Late in life he recalled, “Some years ago I was asked, ‘When you were a kid what did you want to be when you grew up?’ Back then I thought the answer I gave was funny. I said, ‘Saul Bass.’ It was no joke.” He was Saul Bass early; besides excelling in art in high school, he painted signs for local fruit stalls and store windows. A scout for the Art Students League saw some of the signs, found out who made them, and offered Bass a scholarship. He took fine arts courses, but knew what sort of work he wanted to do. “The layout class had a fine-art content, but Saul was happy with the approach, realizing that to be any good at commercial art he had to learn such things as form, color, perspective, and composition.” His first job was for a small commercial art studio that designed trade ads for United Artists; it was just the work he wanted, although film ads in those days had none of the associations with glamour that was to come. “I had no idea anyone looked down upon advertising,” he said. “I looked up to it.” Still, he grew tired of following formulas and “cramming as much illustration, type and hype as you possibly could into ads.” When he took the next job as an art director, he specified that he would not work on movie ads.

Bass was introduced to the Bauhaus theorist György Kepes, who became his mentor and helped change Bass’s work into the strongly Modernist mode, paring away decoration and superfluities. Bass’s firm had trouble with its account for Warner Brothers, and despite his “no movies” stance, Bass was back working on films. In 1946 he realized he had to get out to Hollywood. Movies were changing, not only reflecting the social conditions of the postwar years, but also more films were being made by independent directors and producers. Title sequences of the movies were conventional letters over conventional backgrounds, and sometimes theaters ran the initial credits over the curtain as it went up. Bass thought a film began at the first frame and deserved a mood-setting overture. His title sequences are famous for setting the tone of the film, and are among the best ever made, from the swirling Lissajous patterns of Vertigo to the funny cartoons preceding It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

Bass also did the credits for Psycho, and Hitchcock knew how important integrating Bass’s work into the film was. “Hitchcock involved Saul from the earliest stage. They had meetings before writing began, and Saul received each section of the screenplay as it was completed.” The result was a series of black and white bars on the screen, shifting as if you could almost figure out why, and revealing the words of the credits only when they came infrequently into perfect alignment. It was a signal of dysfunction and uncertainty. Not only did Bass do the titles, he was paid a good fee to “do something” with the shower murder scene, one of the most famous and frightening sequences in all cinema. Bass came up with storyboards that emphasized quick cutting to show a bloody murder in a stylized, frenzied fashion. Hitchcock was reluctant: “I showed it to Hitch. It was very un-Hitchcockian in character. He never used that kind of quick cutting; he loved the long shot.” Bass was even on the set and Hitchcock let him take charge of the filming of the sequence, but Hitchcock when interviewed by François Truffaut six years later was evasive about giving Bass credit.

Bass (and his wife Elaine, who gets much credit in this book for their joint efforts) had a “fade out” from making movie titles. He had a lot of corporate work to do, and was making his own documentaries and film essays (he also directed one feature film, Phase IV). He also found that directors were newly interested in using the title sequence themselves creatively, and perhaps this was a response to his own work. Nonetheless, he came back in the 1990s, working for among others Martin Scorsese (who writes the book’s forward), for whom he did the admirable credits for Goodfellas, Cape Fear, The Age of Innocence, and Casino. Quentin Tarantino gives an interesting analysis of this sort of work, saying that Bass was the greatest of title sequence makers. “I could never do what Scorsese does – give up control of the opening of my film to someone else, not even Saul Bass – I guess I should say Saul and Elaine Bass. I need to keep control of everything and Scorsese is too great a filmmaker not to know the importance of control. It can only mean one thing: Scorsese must have absolute, ab-so-lute, confidence in them. And that is nothing less than amazing to me.”

Among the most interesting pages here are the reproductions of preparatory sketches leading to a final product. Bass would do perhaps 300 sketches for a single simple logo. Shown here are his preparatory drawings for Otto Preminger’s Advise & Consent. The sketches include a Capitol dome with a wind up key, or a faceless congressman with a key in his back, or congressmen as puppets on strings. These are all good. The one Bass and Preminger agreed upon, however, was brilliant, showing the dome of the Capitol tilted open, as if the movie is going to “rip the lid off” the way politics is done. Some of the pictures here show Bass getting ready to make a presentation of his logo work to a particular corporation – there are hundreds of alternative designs on the walls. Bass was a master of the presentation of the final design to corporate clients; he liked being “on stage,” had excellent comedic timing and wit, and connected with each client individually. The presentation was the culmination of intensive work, starting with an analysis of what the company had done, its competitors, and its communication materials, and even enlisting market research. It is significant that Bass thought that one of the most interesting parts of his work was the interviews with one executive at a time. “I get to ask powerful and often interesting people about their work and their lives. It is in their heads that the real blueprint for the future exists or is being formed.”

Bass was devoted to progressive causes, and did plenty of pro bono work; there are designs here for the ACLU, the Special Olympics, Boys Clubs, YWCA, and more. Bass had a devoted family, and people who worked for his firm remembered a dynamic, funny, intense man who loved his job. When they split off to make their own firms, he gave them his blessing – it was part of the creative process, and he had done the same thing himself. To see the many designs in this book is to appreciate that while his work was too diverse to have any one unifying esthetic, it was characterized by simplicity, distillation, and minimalism, and was always forceful because it was so concentrated. Revealingly, he was anxious with every new assignment; he told young designers that “the only difference experience made, he believed, was the knowledge that since one had managed to come up with good ideas in the past, there was good reason to believe it would happen again.” He also said that considering present work is humbling “because no matter how much experience you have, the blank page is still terrifying.” Maybe so, but he conquered any such fears countless times, with successes reproduced here on page after page of memorable, effective images.